Regular readers will know that China Music Radar doesn’t feature an awful lot of bands, however every so often we get provoked into action – particularly where we see an invitation for some juicy commentary.

Second Hand Rose (二手玫瑰) recently announced their “Useless Rock” tour of the East Coast, which features stops in New York, Boston, Washington DC, and (a police station en-route to) Philadelphia.

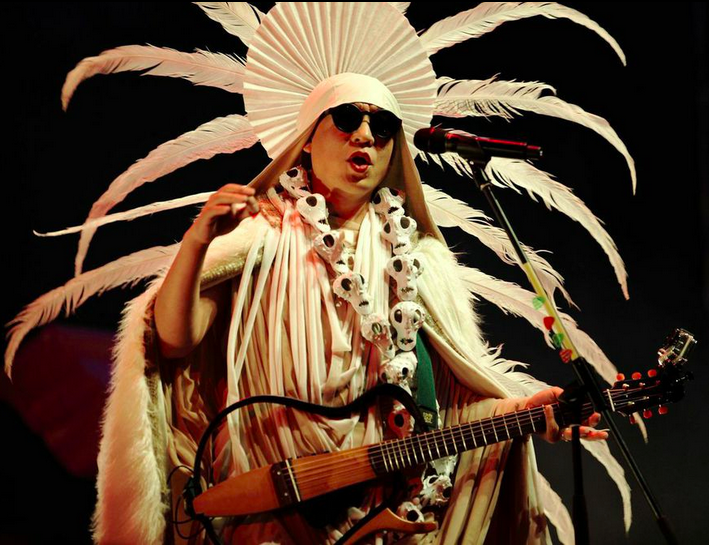

For those new to Second Hand Rose, since their beginnings in 1999 they’ve achieved notoriety through their unique performance style, which has been described as part cabaret, part Chinese theatre, and part “rock ‘n’ roll dance party”. Band members have been known to cross-dress and de-robe at will, causing all kinds of problems for those who unknowingly scramble for front row positions.

In this article we try to transcend the visually stimulating pomp and play, setting our sights instead on presenting the critical edge that enables the band to grapple with a dual challenge: that of offering a message that truly resonates with an audience that grew up among the boom and bust of early Yaogun (Chinese rock n’ roll) and presenting a mercurial energy that prevents the music from taking itself too seriously.

In part 2 we will hear from Eric de Fontenay (of MusicDish*China) who is organising the tour, on themes relating more to the challenges faced when breaking Chinese bands in new territories.

The Uselessness of Rock

The name Second Hand Rose comes from the notion that rock in China is a second-hand and imported endeavour. This is fitting given that it was the dakou (打口) generation that spearheaded the development of modern rock, influenced by imported scrap CDs from the West (where the name originates from).

In a Pledge Music video introduction, the band explains why they chose to name the tour “Useless Rock”:

“Why do we say rock is useless?

Actually it’s not really about debating usefulness, it’s a way to address the values and expressions we see emerging around us. When we say rock is useless we mean its uses are limitless, that’s our main point.”

Elsewhere the band states:

“When we started in 1999 rock was restricted to underground venues. Most bands were countercultural, and almost all disbanded after a few years. In 2000, when we broke through with the line “Buddy, what the heck’re you playing yaogun for?”, we wanted underground rockers to lighten up a little.

Now our question about rock’s usefulness is about keeping its critical edge.”

In this interview with the band’s wonderfully articulated frontman 梁龙 we aimed to level questions that would enable the band to offer their critique in a more explicit way. Some of the issues discussed reflect our own beliefs, and others vamp off ideas that have come up in discussion through other publications on China’s music industry, notably China With a Cut and Red Rock.

Radar:

Authenticity is a key concern for any band. It seems that China’s earliest rock bands took different approaches when ‘importing’ western rock in the early years which included: mimicry, contention (i.e. ignoring foreign expectations and making it your own) and in your case, parody. Why did Second Hand Rose go for the latter? Is the critical approach a reflection of the band members’ personalities, a natural thing, or is there something more to it? Something more calculated?

梁龙:

Many early Chinese rock bands mainly tried to imitate Western examples, which was perhaps inevitable in that phase. We never felt the need to overthrow 颠覆rock. Why go against something you like? But you’re right if you suggest there is a conflict in rock music between on the one hand its adherence of a certain sound and history, defined and dominated by Anglo-American artists, and on the other its call for originality and authenticity. This conflict is especially clear when the musical genre travels outside of its perceived centers, and goes, for instance, to China. Then bands need to be both part of this Western narrative, and somehow also outside of it.

Now, as you point out, we try to overcome this conflict with parody and humor. That’s mainly because humor opens up a space for contradictions to coexist. It enables us to address this, and many other conflicts we experience in our daily lives, without necessarily resolving them. In a nutshell, that’s also what we try to do with our music: address real life issues in an entertaining way, so that people can than pick these issues up and develop their own take on them.

When we first started I hadn’t formulated all of this consciously, but, inspired by earthy Northeastern Chinese stage traditions, it seemed a natural and fun way of dealing with conflicting desires and demands.

Radar:

14 years after establishing, do you think Chinese rock is still seen as “second hand”, or is the post-90s generation (who have grown up in a globalized society) moving beyond the need to locate certain musical styles within a specific geography? Are we living in a ‘cultural free-for-all?’

梁龙:

Things did change a lot. Around 2000 our suggestion that the underground scene had lost contact with the Chinese people, and that most bands were imitating Western examples was controversial, and many reacted strongly. But nowadays rock music in China seems to have joined a global idiom. Young people in big cities are almost instantly connected with developments elsewhere (especially with rock’s perceived centers), and in that sense, we’re approaching a ‘cultural free-for-all’ situation.

At the same time taking inspiration from local traditions has proven to be a successful strategy for making great music, as proven by bands such as Hanggai and Shanren, who engage Mongolian and Yunnan traditions respectively. Rather than an either/or situation, which seemed to be the case ten-odd years ago, today ‘local traditions’ can help open up rock’s creative possibilities and offer it additional tools to connect with people and their lived experiences.

Radar:

Following the last question, do you think a West versus East tension in music still exists? For example, in China bands are done with exhibiting ‘Chineseness’ through rock and moving forward to make the genre their own; is the international crowd behind the curve? What do you think they would expect when they go to see a rock band from China perform?

梁龙:

Instead of framing the issue geographically, let’s try to frame it historically. Great artists in all kinds of arts have continually found inspiration in the past. Add to that that traditions are converging. In the present, cultural differences across the globe are becoming smaller, but many of the places in which that happens have deep roots in very different traditions. The result is an ongoing process of exchange. Western artists have found inspiration in ancient Chinese thought and art, even though they could not always understand it completely. And now the same is happening the other way around.

Our second-handedness signifies a thorough commitment to this process – which we sometimes call ‘bastardization’, after Beijing Bastards 北京杂种, an early rock film with Cui Jian by Zhang Yuan. More recently we are developing the Dialect Art & Music Festival 方言艺术音乐节, which will be a platform for cultural exchange and multiculturalism.

Incidentally, these convictions also undergird our eagerness to tour internationally. It would be easy to be content in the Chinese market. After all, playing internationally comes at a considerable cost, since we obviously can’t get the performance fees abroad that we are able to get in China, yet.

China Music Radar probably has a much better sense of what international audiences may be expecting. But compared to visual art, cinema and even literature, Chinese music seems to lag behind in international recognition. Visual art started with China-themed group exhibitions, only later it became possible for solo artists to exhibit their work individually and without reference to their exotic Chineseness. For music that might still take time. Hanggai is contributing to this development, although they embrace world music and are internationally perceived as Mongolian. We hope to do our bidding as well.

Radar:

Looking at the video of the band playing Drop Around at Mako Livehouse, you’ve got native instrumentation, you are wearing a Han Dynasty Emperor’s Coronet (冕冠), the audience is waving fans… it’s almost like you’re saying to people ‘this is what you want isn’t it? We’re Chinese so our music must be Chinese.’ It’s kind of like a mocking of the old-fashioned glass ceiling the western music industry placed on others who loved rock but happened to live outside its center. It also digs at local bands that try so hard to not be seen as *just* Chinese, who want the music to speak louder than its context. Are we reading this right? Can you add anything to this?

梁龙:

Wearing such an Emperor’s Coronet had basically two meanings.

Firstly it mocks power. A lot has changed in China, like in many other places. A decade or two ago it would perhaps not have been possible to dress up like an emperor. But we thought we could get away with it. It mocks the political and cultural elites, because maybe we are still living under absolutism.

Secondly, like you said, it also challenges Western rock. Not to overthrow Western hegemony or anything, but saying: “we have our own style, we have something to say as well.”

Radar:

Second Hand Rose’s oxymoronic idea that rock is useless by virtue of having so many uses highlights the critical role music plays in enabling youths to construct their identities – each person finds their own use. On the other hand, mass commercialization and branding is hollowing out rock’s meaningfulness as both a genre and tool for identity play. Where are Chinese youths moving to? How do they use music to discover themselves, and what styles are they moving toward? (Still) Post-rock?

梁龙:

Maybe rock is like prostitution. Why do married men go to whore houses? People wondered about this after China had opened up again in the 1980s. The answer was that they need to vent (发泄). Sometime later, let’s say in the early 2000s, it became more acceptable to go to prostitutes. While drinking, men would say: “it costs 300 RMB nowadays, that’s an outrage” and so on. The next step would be complete legalization, after which it would be a normalized and legitimate part of life.

The comparison doesn’t hold entirely, because complete normalization goes against the very nature of rock music. It’s born out of conflict. What is possible, and perhaps even likely, is that rock will gradually dissolve when it loses contact with the conflicts that gave rise to it, or if those conflicts go out of steam. Maybe some of rock’s formal elements will be absorbed by mainstream pop, but as a distinct genre it may disappear. Rock won’t be here forever. Other things might take its place, that’s only natural.

Finally, where the kids are going, is beyond our powers (管不着).

Radar:

Your music and live shows are pretty much untameable. Is this style a means of protecting against the possibility of being co-opted by brands in the same way other underground bands with a more serious tone have been, by the likes of Converse, Vans and Vice etc.? What do you think about bands that depend on brand money to make a living?

梁龙:

Rock won’t be as commercialized as mainstream pop, or at least that’s not something we would be comfortable with. For us it’s not like we are going to wear the shoes of whichever company offers us most money. We are open to working with brands, but want to do so on our own terms. For instance, we recently had a small mix-up with the fashion magazine Elle. Their invitation attests to the fact that rock is getting mainstream acceptance in China. But during the photo shoot it became clear we did not have any opportunity to display our identity and uniqueness. We were just modeling the latest fashion. So we asked them to destroy all the images, which caused some consternation.

Collaboration should be based on mutual understanding. For instance, we recently launched our own fashion line, called Red & Green, inspired by typical Northeastern Chinese colors and prints. Using this concept, we can develop exclusive items in collaboration with brands, even nouveau rich (土豪) brands such as LV or Gucci. That’s something very few musicians can do.

Radar:

What is your hope for the tour? In an ideal world how would you like the U.S. audiences to respond?

梁龙:

We want to provide North-American audiences a more rounded (立体) idea of contemporary Chinese youth culture. We have lived through all this change, have engaged with it through our music and by doing so have actively contributed to a more diverse society, all the while maintaining direct contact with youths living in cities, big and small. So we hope we can offer international audiences unique access and insights. Vice versa, we don’t have any specific expectations of the audience. Maybe some will love it. All in all, touring internationally is part of what this band is about: Chinese, but thoroughly in contact with the world.

The band has set up a Pledge Music crowdfunding campaign, which allows fans at home and abroad to donate toward the tour. Fans can buy tickets to the shows, and pick up items from the band’s clothing line, Red & Green.

The band’s first performance takes place at Modern Sky Festival in Central Park on October 5th. On October 9th the band will also participate in a lecture entitled ” Useless Rock: Youth Culture in the PRC ” at the China Institute, New York, NY. Exciting stuff.

Look out for part two featuring an interview with Eric de Fontenay (of MusicDish*China) who is organising the tour.

[Note: Thanks to fellow band member Jeroen Groenewegen for assisting with editing / translation.]